The Black Douglases of St Bride's Church (Part Three)

A small church in southern Scotland contains the mausoleum of medieval Scotland's most powerful noble dynasty. Let's meet one of them. This is the second chapter of James 'the Black' Douglas.

Hello, I’m Beth! I’m a full time creator based in the Cairngorms in love with Scotland and Scottish history. Subscribers receive weekly newsletters about Scotland’s history and folklore, and a little about my life living and adventuring in this country. If you’d like to support my work as a writer, you can become a paid subscriber.

Interested? Click subscribe…

We left James Douglas in 1307, when he defected from Edward I of England to join the ranks of the outlawed King of Scots, Robert the Bruce. This was a major turning point in his life and career, and for the next 23 years under Bruce, he would develop into one of the most formidable military leaders in Scottish history.

From 1307 to 1308, James regained control of much of southern Scotland alongside Bruce’s brother, Edward Bruce, while Robert campaigned in the north. The first campaign that James led was the recovery of his family lands of Douglasdale and Douglas Castle, setting the tone for the precise, skilled, and brutal warfare that he would quickly master. Attacking the English garrison stationed there on Palm Sunday in 1307 or 1308, Douglas seized back his family home before sacking it to prevent it from falling into English hands again. The slain garrison were piled up in the castle cellar before it was destroyed, and the wells poisoned with salt and the corpses of horses. This gruesome event became known as the Douglas Larder.

Beyond his crucial role in Bruce’s military exploits and control of southern Scotland, it was from 1314 that James Douglas’ reputation truly began to precede him. In addition to his successful seizing of Roxburgh Castle—which involved Douglas and his retinue emerging from the Forest disguised as cattle to get close to the castle—to his knighthood and role at the Battle of Bannockburn, the departure of Edward Bruce to Ireland in 1315 solidified Douglas’ place as King Robert’s primary lieutenant in southern Scotland. Edward Bruce’s death in 1318 further consolidated Douglas’ closeness to Robert alongside the king’s half-nephew, Thomas Randolph. A succession act that same year designated Douglas as second guardian of Scotland behind only Randolph in the event of Robert’s death without an adult heir.

Despite being two ambitious lords and talented military leaders, Randolph and Douglas were successfully managed by Robert with a system of reward for their competitive yet cohesive roles in his administration. Both men were showered with land, title, and appointment for the remainder of Robert’s reign, binding their constant loyalty and obedience to him. It was through Douglas’ relationship with Robert that the Black Douglas powerhouse came to be, their dynastic control of landholding and politics in southern Scotland borne from the Bruce-Douglas allegiance.

During this time, the two characters of Sir James Douglas emerged. ‘The Good Sir James’ was a loyal and talented knight who the king could rely on, a flower of chivalry in Scotland who defended the kingdom. But it was “the Blak Dowglas” who smote England with brutal efficiency, “mair fell than wes ony devill in hell”, as reported by John Barbour. This was to be the moniker that lasted beyond ‘the Good Sir James’, adopted by his descendants who aligned themselves with the terrifying legacy of James ‘the Black’ Douglas.

In the 1310s and 1320s, James Douglas became the principal lieutenant in a new front of warfare: ruthless raids into northern England. While Randolph and Bruce also led raids into England, Douglas mastered them. Penetrating deep into England as far south as the Humber in the east and the Ribble in the west, Douglas’ ravaging of the northern reaches of the kingdom of England caused immense physical, financial and psychological damage. Travelling on hobelars, a type of light horse, the Scots armies carried little and were able to cause maximum damage before disappearing back whence they came.

Douglas became a bogeyman figure in northern England, a terrifying force of evil whom English parents comforted their children against through lullabies. Moreover, the raids had two major factors on this stage of the Scottish Wars of Independence: the extraction of eye-watering amounts of cash and goods to the Bruce regime through truces with local communities in northern England, and the utter humiliation of Edward II of England who was unable to defend his kingdom.

The northern English raids were not Douglas’ only method of being a particularly sore thorn in the side of Edward II. In addition to earlier victories at the Douglas Larder, the Battle of the Pass of Brander, the capture of Roxburgh Castle, and the Battle of Bannockburn, Douglas also played a leading role alongside the likes of Bruce and Randolph at the sieges of Carlisle and Berwick, and in defeating the English on their home soil at the Chapter of Myton, Old Byland, and the Battle of Stanhope Park during the Weardale campaign. Douglas even attempted to capture Edward II of England and his queen, Isabella of France, on not one but two occasions. English accounts claimed that English or Welsh archers who were captured by Douglas were deliberately mutilated, a concentrated and unpleasantly efficient effort to damage the English war machine. At the siege of Berwick, the long fought-over Scottish burgh on the Anglo-Scottish border, Douglas allegedly declared that he would rather enter the town of Berwick than the kingdom of heaven. This was a warlord who terrified his opponents.

There is no denying James Douglas’ formidable strengths as a military leader of the Scottish Wars of Independence, nor that these were strengths that his Black Douglas descendants sought to emulate. In the end, his death would hold just as much a legacy for the Black Douglases as his military career.

In 1329, Robert Bruce, the king who Douglas had so loyally served, died. Before his death, Bruce bequeathed Douglas one final command from king to lieutenant: to take his heart on crusade. This was an honour of great magnitude and a symbol of the personal relationship between Bruce and Douglas, as well as the political and military.

Douglas did as his king requested, leaving Scotland in 1330 to go on crusade with Robert’s embalmed heart in a casket around his neck. Touring through the European continent, Douglas’ retinue joined Alphonso XI of Castile’s campaign against the Emirate of Granada, an independent Islamic state. Douglas’ new Castilian allies were reportedly shocked that the infamous Scottish war leader had no scars on his face, despite his extensive military exploits.

In August 1330, the mighty Black Douglas was killed at the Battle of Teba in Spain alongside most of his Scottish companions. Accounts of the battle claim that when all looked hopeless, Douglas threw Bruce’s heart ahead of him so that he followed his king into death. The symbolism of Douglas’ crusade and death while carrying Robert’s heart would remain powerful, and by 1333 the heraldry of the Douglases had changed to include a bloody heart in recognition of this incomparable relationship. Future generations of the Black Douglases continued to use this heraldry to hark back to the days of Robert Bruce and Sir James Douglas, and the legitimacy of Black Douglas power that began with their bond of allegiance.

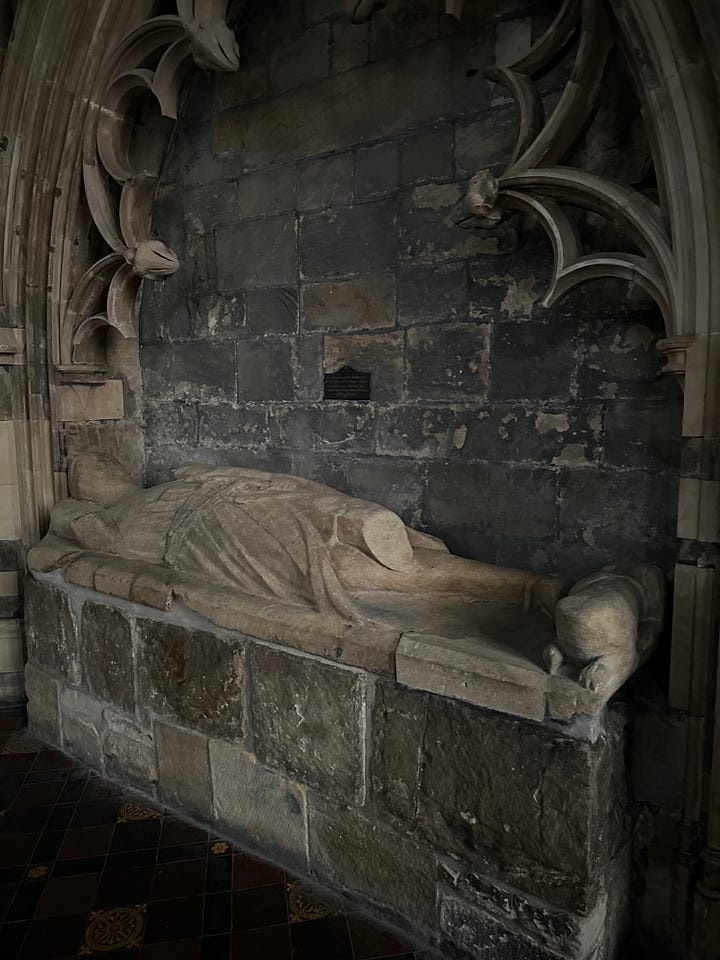

James’ body was returned to Scotland with Robert’s heart. While the king’s heart was interred in Melrose Abbey in the Borders, James found his final resting place at St Bride’s Church in Douglas in the family heartlands that he fought hard to regain and surpassed in status. His son, Archibald ‘the Grim’, would commission a new tomb of alabaster for him during the 1370s, as recorded by Barbour. Although damaged, you can still see this tomb today and stand in the presence of what remains of the almost undefeated Sir James Douglas.

Next week, we’ll move onto another Douglas tomb of St Bride’s Church…

Until then,

Beth xx

Such a rich history - I am loving this series!!

Are you writing a history book Beth? So much researched knowledge and pictures to share. My adoptive parent’s surname was Douglas, loved my ‘dad’ fiercely, and am enjoying learning about the Douglas clan. In this day and age of choice I identify as a Black Douglas - fierce and full of Scottish pride. 🤪😂